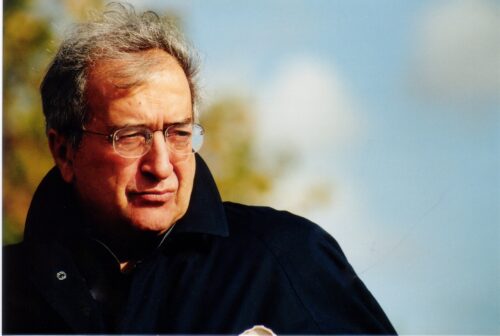

Luciano Berio

© Universal Edition/Eric Marinitsch

Luciano Berio’s biography begins like that of countless Italian (and German and French…) composers of the past: all his ancestors up to the 18th century were musicians. He was born in the small town of Oneglia, where his grandfather and father made their living as church organists and also composed. (Universal Edition has published a selection of their works in the Berio Family Album volume, with pieces by Adolfo and Ernesto along with Luciano Berio.)

While Ernesto Berio was an ardent supporter of the Duce, his son was an equally ardent anti-fascist. Ardent and incensed: he could not forgive Mussolini’s falsification of musical history. The most important, pioneering composers of the 20th century were suppressed, and Berio, who growing up in the provinces was cut off from cultural life anyway, had no access for years to the music that would have been so important to his development.

Berio was convinced that it was essential for young composers to study the scores of the classical masters and to try their hand at different styles. He paid great tribute to his professor Ghedini, who taught him to love and respect Monteverdi’s music (Berio then arranged his Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda in 1966). He also owed much to his friend Bruno Maderna (»I learned, for example, from how he conducted Mozart, or performed my pieces and his own. His knowledge of early counterpoint, Dufay and the others, was enormous, but he also studied electronic music earlier than I did.«)

Berio and Maderna co-founded the Studio di Fonologia Musicale (1955), where Mutazioni, Perspectives and Thema (Omaggio a Joyce), and Différences were produced. Both composers also launched the magazine Incontri musicali (1956–1960) and the concert series of the same name, with conductors such as Boulez, Scherchen, and Maderna. (»We had many enemies. I remember one evening when Boulez was conducting and fisticuffs broke out, so the police had to intervene.«)

In addition to Ghedini and Maderna, Berio also learned a lot from Henri Pousseur, whom he had met in Darmstadt in 1954. »When I look back on those years–he said–I feel gratitude for three people: Ghedini, Maderna and Pousseur. I was, after all, still the young man from Oneglia, and I needed their help to understand much of the music.«)

Over the ensuing years and decades, Berio became one of the defining figures of new music. Much like a small group of composers born in the 1920s (most notably Boulez and Nono), Berio composed works that are considered milestones in the history of new music–whether pieces for solo instruments and voice (the Sequenza cycle), for chamber ensemble (such as Chemins, based on some of the Sequenze), orchestra (Sinfonia, where the orchestra is joined by eight solo voices, is still a representative work of the 60s), for choir and orchestra (Coro is an emblematic exploration of folk music), for voice and orchestra (like Epiphanies), solo voice, choir and orchestra (Stanze for baritone, male choir and orchestra was Berio’s farewell to composing) and all his works for musical theater (Passaggio, La vera storia, Un re in ascolto, Laborintus II…. ).

Berio never lost sight of his musical predecessors. His reconstruction of an unfinished Schubert symphony in rendering, his arrangements and orchestrations of Purcell, Boccherini, de Falla, Verdi, Mahler, Puccini, Weill testify to this. He also kept his ears open to music outside the concert hall and the opera house: he was an admirer of the Beatles and put some of their hits into arrangements. His orchestration of a bouquet of folk songs from various nations (Folk Songs) became a hit in its own right.

Luciano Berio was aware of his responsibility as a member of society. He said he had no sympathy for composers who thought they were mouthpieces of the universe and humanity. »I think it is enough if we strive to become responsible children of society.«